10/25/2017

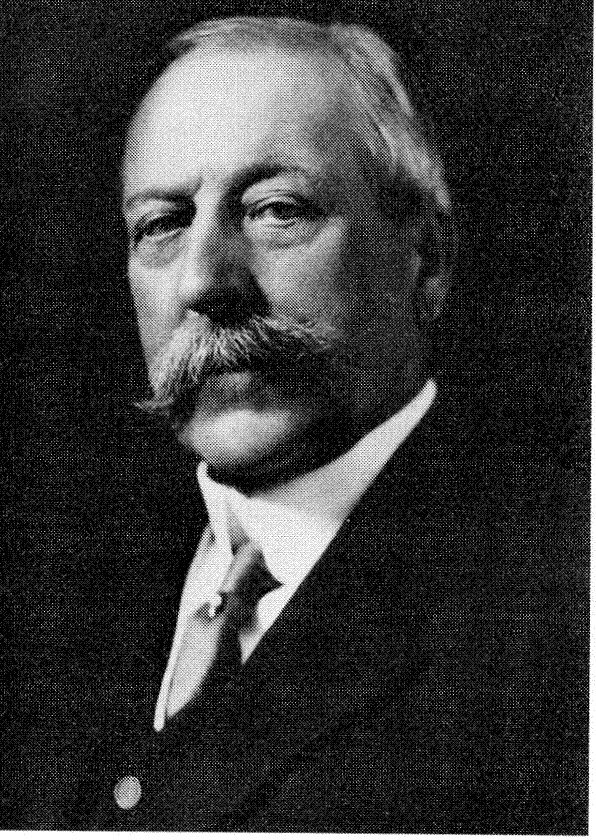

COMMODORE FERGUSON

Walton Ferguson served the Stamford Yacht Club as Rear Commodore (1897-1898), Vice Commodore (1899-1903) and Commodore (1904-1907), and later returned for an additional year as Rear Commodore (1911). His tenure as a flag officer exceeds that of any other SYC member by at least four years. He was elected a member of New York Yacht Club in 1887.

Ferguson’s catboat, Tigress, raced in the Yale-Harvard Regatta of 1894. Records suggest that he then became fascinated with powerboats. He acquired the steam launch Myosotis in 1895, the steam yacht Ava in 1901, and the 164’ steam yacht Christabel in 1909.

Commodore Ferguson’s grandfather immigrated to Philadelphia in 1790, from County Yorkshire, England. He later moved to New York City and opened a shipping business with his brother-in-law. By 1802, it had evolved into the merchant banking firm of J&S Ferguson. In 1816 the firm was inherited by Walton’s father, John Ferguson (born in NYC on April 23, 1803), who moved it to 35 Pine Street in the financial district. John Ferguson and his wife, Helen Morewood Ferguson (born in NYC in 1806), moved to Stamford from New York City in 1842. John Ferguson was also one of the organizers of the Stamford Gas-Light Company in 1854.

Walton was born in Stamford on July 6, 1842 and attended Trinity College until leaving because of illness. He joined the family business in 1863. On September 7, 1869, he married Julia Lee White (born in NYC on January 20, 1846) in Stamford. She was the daughter of John Trumbull White of Hartford and Sarah Grace Carroll of New York City.

J&S Ferguson had thrived by investing in clipper ships, marvels of the 19th century which could transport valuable cargo at 250 miles a day by cutting through the waves rather than riding over them. The firm accumulated exclusive U.S. distribution rights on a number of foreign products. One of these was “Henry’s Calcined Magnesia,” which was produced by pharmacist-brothers William and Thomas Henry in Manchester, England. At the time, calcined magnesia was considered a crude and distasteful remedy, and was subject to a specific import duty rate, while the rate on more palatable medicines was more than four times higher. When the Fergusons were ordered to pay the higher rate, Walton sued for relief and, after losing in the lower courts, finally took his argument to the U.S. Supreme Court in Ferguson v. Arthur 117 US 482 (1886). The Justices upheld the primary court’s ruling that, due to additives and special processing, Henry’s Calcined Magnesia simply tasted too good to be taxed as ordinary calcined magnesia. It is hard to imagine a more valuable product endorsement, but the higher tax must have put Henry’s at a competitive disadvantage to Husband’s Calcined Magnesia, which was considered the leading domestic brand.

Does the story above relate to Phillips’ Milk of Magnesia, which was invented in Stamford and took over the market? We find no documented connection between Walton Ferguson and Charles Henry Phillips (1820-1882), the British pharmacist who obtained the patent for Milk of Magnesia in 1873. Phillips, whose grandson became our Commodore in 1935, resided at 666 Hope Street, in the Glenbrook section of Stamford, not far from the Ferguson home on Strawberry Hill. When he died, his four sons took over the business and the product, which Sterling Drug acquired from the family in 1923. It continued to be manufactured in Glenbrook until 1976. It is, at least, an interesting coincidence.

J&S Ferguson diversified and sought to use its capital in the most promising industries of the time, so Walton and his brother, Edmund, moved to Pittsburgh and began accumulating mining interests throughout western Pennsylvania. They became prominent figures in the field, so Henry Clay Frick sold shares of his coal and coke production company to them, and then made them his partners. A few years later, the H.C. Frick Coke Company became the exclusive provider of coke for Andrew Carnegie’s steel mills.

Walton eventually returned home, and became president of the Stamford Gas-Light Company. (Interesting note: Until 1872, the company had turned off the entire gas supply during the day because it was used only for lighting.)

When electricity emerged as a competing energy medium, a group of Stamford businessmen formed the Stamford Electric Lighting Company. They sat on their exclusive charter from 1881 until 1886, and then began competing for the City’s street lighting contracts, which they monopolized by 1890. Little wonder that the company’s top three officers were in a position to be incorporators of the Stamford Yacht Club that year!

Ferguson responded by pressing for a merger of the companies. In July 1893, he was named President of Stamford Gas and Electric Company, which he ran for the next 24 years.

Ferguson was also President of St. John Wood-Working Company, Vice President of Stamford Trust Company, and a director of Union Carbide and other major corporations in Connecticut, New York City, and elsewhere. He was an organizer of Brooklyn Edison, a founding director of the Stamford Board of Trade, president of the Ferguson Library, and vestryman, warden and senior warden of St. John’s P.E. Church.

The Commodore owned many properties in Stamford, but his purchase of the late Colonel Waring’s property on Main Street in September 1902 is worth noting. The sale, including 100 feet of frontage, was “one of the biggest deals in the Stamford realty market in a long time.” The price was not disclosed, but was rumored to be about $25,000.

In 1903, Mayor Leeds named Walton Ferguson to Stamford’s Appropriations Committee, not once, but several times. The Common Council, though fellow Republicans, resisted the appointment and almost brought Stamford Government to a standstill. It was believed this was in retaliation for the Mayor having appointed William H. Brennan as acting Chief of Police without consulting the Council.

Walton and Edmund Ferguson bought most of Fishers Island in 1891. It had been granted to John Winthrop in 1640 and owned but largely ignored by his descendants for over 200 years until it was purchased by Robert Fox in 1863. A second generation of his family began developing tourism there in 1876. When the Fergusons bought it, they discouraged tourism, and began turning the island into a planned community of fine homes and golf courses. The Fergusons maintained a profitable monopoly of the hotel and rental markets, as well as the ferry, electrical, telephone and water services.

Seven years after the Ferguson purchase, the Federal Government determined that the southeastern portion of Fishers Island was strategically valuable as a “Gibraltar-like” outpost for the defense of New York City and communities on Long Island Sound. In 1898, after a protracted lawsuit, the Government successfully acquired a portion of the island. It was the first of a series of such purchases, the last of which occurred in 1943. The land was taken out of military use after World War II, and distributed and auctioned to the public over the following decade.

Walton’s oldest brother, John Day Ferguson, practiced law in New York City for some time, and was then elected to represent Stamford in the State legislature, where he was a member of the Education Committee. He later served as Stamford’s Probate Judge for three years. He was so dedicated to the improvement of Stamford’s schools that they were closed in his honor on December 12, 1877, the day of his funeral. He died at age 45, and left a bequest of $10,000 for the building of a public library, conditioned on the raising of an additional $25,000 for the same purpose. The Ferguson Library opened in January 1882.

The two remaining Ferguson brothers, Henry and Samuel, are memorialized in A Furnace Afloat: The Wreck of the Hornet and the Harrowing 4,300-mile Voyage of its Survivors, by Joe Jackson. Samuel Ferguson was dying of tuberculosis at the age of 28 and it was hoped that he would be comforted, though probably not saved, by sailing to the west coast for a change of climate. He was accompanied by his brother Henry, age 18, aboard a clipper carrying candles and kerosene to California. On May 3, 1866, while the Hornet was 1,000 miles west of the Galapagos Islands and nearly four months into its trip, a crew member’s lantern caused an explosion below decks and set the ship afire. An officer was assigned to each of the three lifeboats, which were loaded with crew and supplies. Food and water were shared with strict fairness. When it ran out, the men lived on rainwater and caught fish, when these were available, and chewed clothing and canvas when they were not. The boats traveled under makeshift sails, guided by compasses, without charts. They were tied together for 18 days, but that threatened to pull the boats apart in rough seas. After casting off the connecting lines, they remained in each other’s sight for another few days and then became separated. The longboat, which held the captain, the Fergusons and 12 crew members, sighted Mauna Loa on the 43rd day, having traveled 2,500 miles from the Hornet’s sinking. The other two boats were lost at sea.

While Henry and Samuel were regaining their strength in Hawaii, they were interviewed by a young journalist for a Sacramento newspaper, Samuel Langhorne Clemens, who first became famous by reporting their story.

Later in the summer, the Ferguson brothers completed their trip to California, where Samuel died of tuberculosis on October 1, 1866.

Walton and Julia Ferguson donated the Edward Ferguson Memorial building in St. Luke’s Chapel and the Lamb of God Rose Window in St. John’s Episcopal Church in memory of their son, Edward, who died at age 14 on October 16, 1890, the day on which the Stamford Yacht Club was organized. Edward is buried in Woodland Cemetery, along the eastern leg of Stamford Harbor.

The interweaving of our flag officer biographies is not limited to business affairs. Alfred W. Dater (Rear Commodore 1925-27) was married to Grace Carroll Ferguson (the Commodore’s daughter) and became Chairman of Stamford Gas and Electric. The firstborn of their three sons was named Walton Ferguson Dater (1899-1972).

Another child of the Commodore, Walton, Jr., is best remembered as a long-time member and former president of the Westminster Kennel Club, which still awards a major trophy in his name. He was a competitive motor boater, as well. The New York Times of September 16, 1905 tells us the Race Committee on the previous day failed to score Ferguson’s finish time, while he claimed to have earned first place. “Mr. Ferguson states that the officials had gone to eat and he offers to produce one hundred or more persons who saw his boat finish.” It was a very different age in many ways, but some things never change.

Three sons and two daughters were born to Walton and Julia in Stamford, between 1870 and 1879. The two not previously mentioned were Helen Gracer Ferguson and Alfred L. Ferguson. A fourth son, Henry Lee Ferguson, was born in Pennsylvania in 1881.

Commodore Ferguson died on April 7, 1922. Mrs. Ferguson died on August 26, 1933. They are buried in Stamford’s Woodland Cemetery, with all six of their children and other family members.

CJHynes